If you just want the answer to the question posed in the title, click the TLDR below and then move on with your day. Otherwise, buckle in, we’re going debugging; this post is mostly about my thought process and techniques I used to arrive at the answer rather than the answer itself.

TLDR: Just tell me why CDC Ethernet doesn't work on Android

Android's EthernetTracker service only acknowledges interfaces that are named ethX; Linux's CDC Ethernet drivers create interfaces that are named usbX. There is no way to work around this, short of rooting the phone to change the value of config_ethernet_iface_regex.

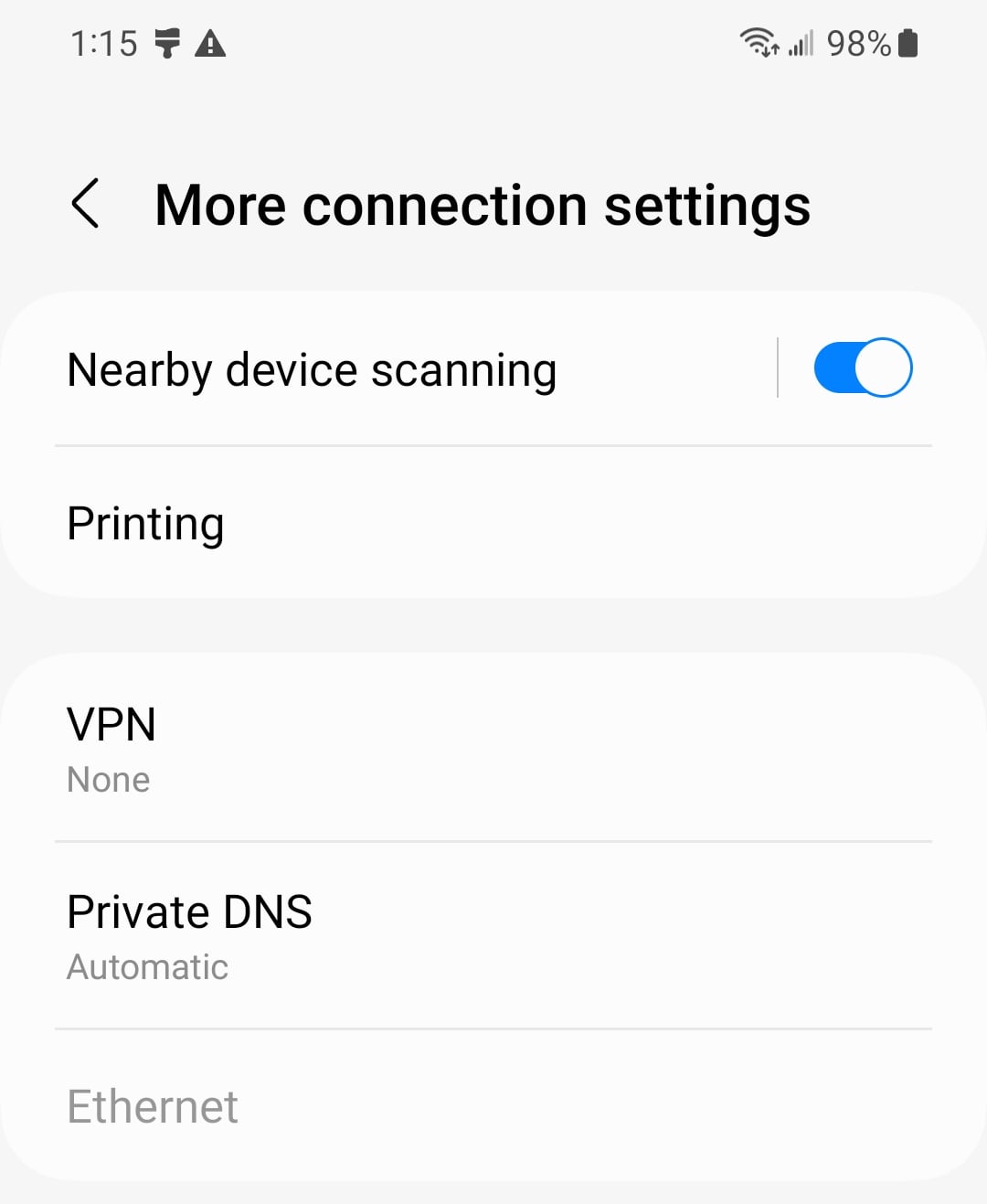

Android contains support for USB ethernet adapters. There’s even menus for them!

This means that if you very carefully select a USB Ethernet adapter that you know has a chipset compatible with your Android device, you can plug it in and these settings will spring to life. How do you know what chipsets are compatible with your phone?

Hearsay!

I’m not entirely kidding. If the company that you bought your phone from sells a USB ethernet adapter as an accessory to it, you have a pretty good chance of that one working. Otherwise, it’s hit-or-miss; phone manufacturers rarely, if ever, publish lists of supported Ethernet adapters. The best you’re going to get is finding a forum post from someone that has the same phone as you saying that they bought a particular adapter that worked, and hoping you can find the same thing to buy.

Or is it?

As you may know, if you dig deep beneath Android’s Googly carapace, you’ll find a Linux kernel. To build the Linux kernel, you must first configure it. This configuration determines what features and hardware the resulting kernel will support. Thus, the list of Ethernet adapters supported by your phone will more-or-less correspond to those selected in the kernel configuration for your phone, although it’s possible (but unlikely) that your phone’s manufacturer doesn’t ship all of the drivers that they build, or that they build additional third-party drivers separately.

So, in order to figure out what Ethernet adapters your phone supports, you’re going to want to find your phone’s kernel configuration. How do we do that?

First, enable USB debugging and install ADB

If you’d like to follow along with this blog post, you’re going to need enable USB debugging and to install ADB (Android Debug Bridge) — this is a command-line tool that is used by developers to interact with Android devices. In this post, we will be using it to run shell commands on a phone.

There’s good documentation elsewhere on how to do these things so I’m not going to waste time by rewriting it poorly. Instead, have some links:

- First, enable USB debugging on your phone

- Install ADB on your computer

- Run

adb shell, which will give you a shell prompt on the phone.

Congratulations, you can now run commands on your phone. Type exit and press enter when you’re ready to exit the ADB shell.

Next, we need to switch things up so that ADB connects to the phone over the network, instead of via USB. We need to do this because we’re going to try plugging some network adapters into the phone’s USB port, so we can’t also use the port for debugging.

With your phone connected to your computer via USB:

- Connect your phone to the same network as your computer via wifi

- Figure out your phone’s IP address - you can do this by digging around the Settings app, or you can try

adb shell ifconfig wlan0 - With the phone still connected via USB, run

adb tcpip 5555 - Disconnect the USB cable from the phone

- Reconnect to the phone by running

adb connect YOUR_PHONE_IP:5555(replacing YOUR_PHONE_IP with the IP address from the phone) - Try

adb shellto make sure it still works

Once you have ADB working over the network, you can proceed with trying to figure out what version of the kernel your Android device is running.

If you have a newer phone…

These days, Google publishes an Android Common Kernel, which downstream phone manufacturers are required to derive their kernels from. The source to this kernel is hosted in a Git repository at googlesource.com.

If your phone shipped with Android 11 or later, you have something called a GKI kernel - in this case, Google builds the kernel and the phone manufacturer puts all of their model-specific secret sauce into kernel modules. In this case, you can find the configuration that Google is using by navigating to the appropriate branch of the kernel repository, and looking at the file arch/$ARCH/configs/gki_defconfig, where $ARCH is the processor architecture of your phone. For example, if your phone has a 64-bit ARM processor (and it almost certainly does) then you will find this configuration at arch/arm64/configs/gki_defconfig.

How do I find out for sure what kernel version and processor architecture my phone has?

Now that we have the ability to run shell commands on the phone, we can turn to good old uname to discover the kernel version and architecture that’s currently running.

- Go back and enable USB debugging and install ADB, if you haven’t arleady

- Run

uname -aon the phone, either by runningadb shelland then runninguname -a, or all in one go by runningadb shell uname -a.

You should get output something like this:

Linux localhost 4.19.113-26203352 #1 SMP PREEMPT Tue Apr 18 16:05:51 KST 2023 aarch64 ToyboxYou’ll the kernel version in the third field and the architecture in the second-to-last; you’ll have to make an educated guess about which branch or tag in Google’s kernel repository corresponds to the one running on your phone.

What if I have an older phone?

If you have an older phone, then you’re in the same boat as me; I have an iPhone as a daily driver, but I keep a Samsung Galaxy s20 around as an Android testbed. Unfortunately, the s20 shipped with Android 10, which is the version just before all of this standardized kernel stuff from Google became required. Even though the s20 has since been upgraded to Android 13, Google doesn’t require phone manufacturers to update the kernel along with the Android version, and so Samsung didn’t; it still runs a kernel based on Linux 4.19.

In this case, you need to get the kernel configuration from your phone manufacturer, so you’d better hope they’re actually doing regular source releases. Samsung does do this; you can find sources for their phones at opensource.samsung.com.

Once you have the sources for your device, you’re going to have to dig around a bit to figure out what kernel config. The sources I obtained for my phone from Samsung included a Kernel.tar.gz; inside of this archive was a Linux kernel source tree, along with a few additions. One of those additions was a shell script called build_kernel.sh, which goes a little something like this:

#!/bin/bash

export ARCH=arm64

mkdir out

BUILD_CROSS_COMPILE=$(pwd)/toolchain/gcc/linux-x86/aarch64/aarch64-linux-android-4.9/bin/aarch64-linux-android-

KERNEL_LLVM_BIN=$(pwd)/toolchain/llvm-arm-toolchain-ship/10.0/bin/clang

CLANG_TRIPLE=aarch64-linux-gnu-

KERNEL_MAKE_ENV="DTC_EXT=$(pwd)/tools/dtc CONFIG_BUILD_ARM64_DT_OVERLAY=y"

make -j8 -C $(pwd) O=$(pwd)/out $KERNEL_MAKE_ENV ARCH=arm64 CROSS_COMPILE=$BUILD_CROSS_COMPILE REAL_CC=$KERNEL_LLVM_BIN CLANG_TRIPLE=$CLANG_TRIPLE vendor/x1q_usa_singlex_defconfig

make -j8 -C $(pwd) O=$(pwd)/out $KERNEL_MAKE_ENV ARCH=arm64 CROSS_COMPILE=$BUILD_CROSS_COMPILE REAL_CC=$KERNEL_LLVM_BIN CLANG_TRIPLE=$CLANG_TRIPLE

cp out/arch/arm64/boot/Image $(pwd)/arch/arm64/boot/ImageIf you squint at this long enough, you’ll spot a reference to something that looks like a kernel config: vendor/x1q_usa_singlex_defconfig. There isn’t a subdirectory called vendor in the root of the archive, so I used find to figure out exactly where the file lives:

$ find . -name x1q_usa_singlex_defconfig

./arch/arm64/configs/vendor/x1q_usa_singlex_defconfigAha, there it is, deeply nested in a subdirectory.

Finding the kernel config sounds hard, is there an easier way?

There might be, if you’re lucky! Give this a shot:

$ adb shell zcat /proc/config.gzIf you’re lucky, and your phone manufacturer has enabled the relevant kernel option, then a compressed copy of the configuration that your kernel was compiled with is available at /proc/config.gz. If this is the case, you’ll have a large amount of output streaming to your terminal. You probably want to redirect it somewhere so you can peruse it at your leisure:

$ adb shell zcat /proc/config.gz > my_kernel_configIf you’re unlucky, you’ll see something like this:

zcat: /proc/config.gz: No such file or directoryIn this case, there is no easy way out; you’ll have to refer to the sources your phone’s kernel was built from.

What does a kernel configuration look like?

In case you’re interested, here is the kernel configuration for my Galaxy s20: x1q_usa_singlex_defconfig

Your kernel configuration should look very similar to this, but not identical, unless you have the same phone that I do.

OK, I have the kernel configuration for my phone, what now?

For the purpose of determining which USB Ethernet adapters the kernel supports, most of the configuration variables that we are interested will start with USB_NET, so just grep the kernel configuration for that string:

$ grep USB_NET my_kernel_config

CONFIG_USB_NET_DRIVERS=y

CONFIG_USB_NET_AX8817X=y

CONFIG_USB_NET_AX88179_178A=y

CONFIG_USB_NET_CDCETHER=y

CONFIG_USB_NET_CDC_EEM=y

CONFIG_USB_NET_CDC_NCM=y

# CONFIG_USB_NET_HUAWEI_CDC_NCM is not set

... and so on ...Look for a CONFIG_USB_NET_something that looks like it relates to the chipset of the adapter you want to use. The best news is if it is set to y; that means the driver is built-in to your kernel and that your phone’s kernel definitely supports that chipset. If it’s set to m, that’s still probably good news; that means that the driver was compiled as a module when your kernel was built, and that the module is likely loadable on your phone unless your phone’s manufacturer specifically left it out. If you see is not set, then that is the worst news; the driver was neither built-in to your kernel, nor was it compiled as a module, so it’s likely not available for you to use.

If you’re having trouble figuring out which configuration items correspond to which chipsets, have a look at drivers/net/usb/Kconfig in your kernel tree. This file will contain extended descriptions of each configuration item.

Unfortunately, to figure out which chipset a particular adapter uses, you’re mostly back to hearsay; few manufacturers of USB Ethernet adapters explicitly advertise which chipset they use.

So what’s this about CDC Ethernet and why should I care?

CDC stands for Communications Device Class. This is a set of interrelated standards that manufacturers of USB devices can follow; among them are a trio of standards called EEM (Ethernet Emulation Model), ECM (Ethernet Control Model), and NCM (Network Control Model) that can be used to build USB Ethernet adapters. Most of the difference between these three standards is a matter of complexity; EEM is the simplest to implement and is easy to support on underpowered devices, but may not result in the best performance. ECM is more complex to implement for both the USB host and the device, but promises better performance than EEM; NCM is a successor to ECM that promises even higher speeds. Many devices implement more than one of these protocols, and leave it up to the host operating system to communicate with the device using the one that it prefers.

The point of these standards is that, assuming manufacturers follow them, operating systems can provide a single common driver that works with a variety of drivers. You generally don’t need special drivers for USB keyboards or mice because of the USB HID standard; the USB CDC standard attempts to accomplish the same for USB networking devices.

One particularly fun thing is that Linux implements both the host and the device side of the CDC Ethernet standards. That means that if you have hardware with a USB OTG port, which is common on the Raspberry Pi and other small ARM devices, you can tell the kernel to use that port to pretend to be an Ethernet adapter. This creates a USB network interface on the host that is directly connected to an interface on the guest; this lets you build cool things like embedded routers, firewalls, and VPN gateways that look like just another Ethernet adapter to the host.

Linux, as well as Windows and macOS (but not iOS) include drivers for CDC Ethernet devices. Unfortunately, none of this works on Android devices, despite Android being based on Linux. Why is Android like this?

Based on the kernel configuration, Android appears to support CDC

Let’s have another look at our kernel config, and grep for USB_NET_CDC:

$ grep USB_NET_CDC my_kernel_config

CONFIG_USB_NET_CDCETHER=y

CONFIG_USB_NET_CDC_EEM=y

CONFIG_USB_NET_CDC_NCM=y

... and so on ...Here we can see that Samsung has built support for all 3 CDC Ethernet standards into their kernel (CONFIG_USB_NET_CDCETHER corresponds to ECM). Google’s GKI kernels are somewhat less generous and appear to leave out ECM and NCM, but still include support for EEM as a module.

I’ve got a device with an OTG port that I’ve configured as an Ethernet gadget. It works when I plug it into my Mac. It works when I plug it into my Ubuntu desktop. It even works when I plug it into my Windows game machine (actually the same computer as the Ubuntu desktop, booted off of a different drive 😁). It doesn’t work at all when I plug it into my Galaxy s20. The Ethernet settings are still greyed out:

Let’s grab a shell on the phone and dig in a bit.

The Linux kernel exposes information about itself in a pseudo-filesystem called sysfs - this looks like a directory tree full of files, but reading the files actually gets you information about the current state of the kernel.

Among other things, sysfs contains a directory named /sys/class/net, which contains one entry for every network interface that the kernel is aware of. Let’s connect our Ethernet gadget to the phone and see if anything shows up there:

$ adb shell ls /sys/class/net

... lots of output ...

usb0

wlan0Could usb0 be the gadget? Let’s use ifconfig to check it out:

$ adb shell ifconfig usb0

usb0 Link encap:UNSPEC Driver cdc_eem

BROADCAST MULTICAST MTU:1500 Metric:1

RX packets:0 errors:0 dropped:0 overruns:0 frame:0

TX packets:0 errors:0 dropped:0 overruns:0 carrier:0

collisions:0 txqueuelen:1000

RX bytes:0 TX bytes:0That certainly looks like our gadget. Too bad the interface is down. Unfortunately, the Ethernet settings on the phone are still greyed out:

Let’s unplug the gadget and make sure usb0 goes away when we do:

$ adb shell ls /sys/class/net | grep usb

$ # no outputYep, it’s gone.

It looks like we’re using EEM mode. In addition to the g_ether module, Linux also includes a thing called configfs that can be used to create custom gadgets. Let’s try one that only supports ECM and see if that works:

$ adb shell ls /sys/class/net | grep usb

usb0

$ adb shell ifconfig usb0

usb0 Link encap:UNSPEC Driver cdc_ether

BROADCAST MULTICAST MTU:1500 Metric:1

RX packets:0 errors:0 dropped:0 overruns:0 frame:0

TX packets:0 errors:0 dropped:0 overruns:0 carrier:0

collisions:0 txqueuelen:1000

RX bytes:0 TX bytes:0

It’s still detected, but it’s still down. Will NCM fare any better?

$ adb shell ls /sys/class/net | grep usb

usb0

$ adb shell ifconfig usb0

usb0 Link encap:UNSPEC Driver cdc_ncm

BROADCAST MULTICAST MTU:1500 Metric:1

RX packets:0 errors:0 dropped:0 overruns:0 frame:0

TX packets:0 errors:0 dropped:0 overruns:0 carrier:0

collisions:0 txqueuelen:1000

RX bytes:0 TX bytes:0

No, it will not.

So why doesn’t CDC work on Android?

At this point, we’ve more-or-less established that everything is fine on the kernel level. I’m pretty sure that if I wanted to, I could root this phone, manually configure the interface with ifconfig, and it would pass traffic just fine. That means the problem must be somewhere in the stack of software above the kernel.

If this was a regular Linux system, this is the point where I’d start poking at systemd-networkd, or NetworkManager, or ifupdown, depending on the particulars. This is not a regular Linux system, though; it’s an Android device, and none of that stuff exists here. What do I know about how Android configures network interfaces?

NOTHING. I know nothing about how Android configures network interfaces. How do we figure this out?

Well, Android is at least sort of open source; many of the good bits are closed behind the veil of something called “Google Play Services” but maybe there’s enough in the sources that are released to figure this out.

To play along with this bit, you’ll need to download the source to Android. This is a whole process on its own, so I’ll leave you to Google’s documentation for this, except to note that you’ll need a special tool called repo. This seems to be meant to make it easier to download sources from multiple Git repositories at once; sometimes it feels like I’m the only person that actually likes Git submodules. There are a lot of sources to download, so start this process and then go knock off a few shrines in Zelda while it wraps up.

I figure that searching for the string Ethernet is probably a good starting point. Because there is so much source to go through, I’m going to skip vanilla grep this time and enlist the aid of ripgrep. There’s a lot of configuration files and other clutter in the Android sources, as well as most of a Linux distro, but I know that any code that we’re going to care about here is likely written in Java, so I’m going to restrict rg to searching in Java files:

$ rg -t java Ethernet

... SO MUCH OUTPUT ...At this point, there’s not much else to do but look at the files where we’ve got hits and try to figure out what part of the code we can blame for our problem. Fortunately for you, I’ve saved you the trouble. After reading a bunch of Android code, I’m certain that our culprit is EthernetTracker.java. This appears to be a service that listens on a Netlink socket and receives notifications from the kernel about new network interfaces. The EthernetTracker contains a method that determines if an Ethernet interface is “valid”; if it is valid, the EthernetTracker reports to the rest of the system that an interface is available, and the Settings app allows the interface to be configured. If an interface is not valid, then the EthernetTracker simply ignores it.

How does the EthernetTracker determine if an interface is valid?

private boolean isValidEthernetInterface(String iface) {

return iface.matches(mIfaceMatch) || isValidTestInterface(iface);

}With a regex, of course.

Where does this regex come from?

// Interface match regex.

mIfaceMatch = mDeps.getInterfaceRegexFromResource(mContext);It comes from a method called getInterfaceRegexFromResource. Where does that method get it from?

public String getInterfaceRegexFromResource(Context context) {

final ConnectivityResources resources = new ConnectivityResources(context);

return resources.get().getString(

com.android.connectivity.resources.R.string.config_ethernet_iface_regex);

}There’s actually a nice comment at the top of the file that explains this:

/**

* Tracks Ethernet interfaces and manages interface configurations.

*

* <p>Interfaces may have different {@link android.net.NetworkCapabilities}. This mapping is defined

* in {@code config_ethernet_interfaces}. Notably, some interfaces could be marked as restricted by

* not specifying {@link android.net.NetworkCapabilities.NET_CAPABILITY_NOT_RESTRICTED} flag.

* Interfaces could have associated {@link android.net.IpConfiguration}.

* Ethernet Interfaces may be present at boot time or appear after boot (e.g., for Ethernet adapters

* connected over USB). This class supports multiple interfaces. When an interface appears on the

* system (or is present at boot time) this class will start tracking it and bring it up. Only

* interfaces whose names match the {@code config_ethernet_iface_regex} regular expression are

* tracked.

*

* <p>All public or package private methods must be thread-safe unless stated otherwise.

*/Let’s go back to ripgrep to see if we can skip to finding out what config_ethernet_iface_regex is:

$ rg config_ethernet_iface_regex

...

frameworks/base/core/res/res/values/config.xml

410: <string translatable="false" name="config_ethernet_iface_regex">eth\\d</string>

...

packages/modules/Connectivity/service/ServiceConnectivityResources/res/values/config.xml

170: <string translatable="false" name="config_ethernet_iface_regex">eth\\d</string>

...…and there it is. The default value of config_ethernet_iface_regex is eth\d; in regex parlance, that means the literal string eth, followed by a digit.

The kernel on the phone calls our CDC Ethernet gadget usb0. This doesn’t start with the string eth, so EthernetTracker ignores it. Unfortunately, this setting is not user-configurable, although you can hack it by rooting the phone.

It really is that silly; an entire USB device class brought low by a bum regex.

Is it a bug?

I can’t tell if this is intentional or not; it feels like an oversight by Google, since even the newest GKI kernels apparently go out of their way to include support for EEM adapters, but because the interface name doesn’t match the regex, the kernel’s support for EEM adapters is unusable. This puts you in a rather perverse situation when shopping for USB Ethernet adapters to use with Android; instead of looking for devices that implement the CDC standards, you need to explicitly AVOID the standards-based devices and look for something that is supported with a vendor/chipset-specific driver.

Thanks for playing!

I hope you enjoyed going on this journey with me, or even better that I saved you from duplicating my efforts. Perhaps if I am feeling feisty, I will try to figure out how to submit a patch to Android to change that regex to (eth|usb)\d in the next few weeks. If a real Android dev or someone at Google reads this and beats me to the punch, I owe you the beverage of your choice.